5 min read

In Part 1: Evaluating Spatial Audio – Criteria & Challenges, we talked about what constitutes a ‘spatial audio’ product system, the key challenges involved, objective and subjective means of evaluation, and some of the key spatialization parameters to pay attention to. Make sure you check out that blog post, as this piece builds on the concepts covered in that one.

As a quick refresher, ‘Spatial Audio’ is a broad umbrella term that is used to describe an array of audio playback technologies, where the primary focus is to enable the listener to listen and experience sound as we do in the real world – in three dimensions.

It is also important to mention that spatial audio is an inherently subjective psychoacoustic phenomenon that differs greatly from person to person, based on their physiology. Everyone has their own set of ears and physiology, unique to them, and accordingly, our hearing systems and unique subjective listening experiences are finely tuned by our own specific anatomy. You can read more about spatial audio here.

Thus, without even getting too far into the weeds when it comes to file formats, channel orders and configurations, content specific requirements etc., we can see that the inherent subjectivity of the perceived experience makes evaluating spatial audio difficult.

There seems to be a lack of an industry standard framework to evaluate the spatial audio experience. Here at Ceva, we set out to develop such a framework, to evaluate spatial audio in a systematic and repeatable way, providing a guide for anyone to be able to gauge the efficacy of a spatial audio solution.

We started by limiting ourselves to the form factor of Android phones and True Wireless Stereo (TWS) earbuds, amassing a few different options to compare. Having established the parameters we wanted to test, we then conducted a competitive analysis between the various options. In this blog post, we will focus on the content used, and the philosophy that went into curating some of it.

Creation and Selection of Content

One important tool in any audio engineer’s arsenal is having a curated selection of content for testing purposes. Anyone can learn from this habit, as the key here is that it must be audio that one is intimately familiar with, in terms of how it sounds. Thus, referencing it on a variety of playback systems reveals a lot of useful information, as one’s ears have a deep understanding of what it is supposed to sound like.

(Source: Ceva)

So how does one go about selecting this content? Before we answer that question, it is important to understand what different sounds can reveal to us, especially in terms of aspects such as frequency content, or dynamics. For example, an audio clip of pink noise is always handy, as pink noise is basically noise that contains all frequencies that our ears can perceive, with the energy equally dispersed across each octave band of frequencies. It sounds a lot like sounds we are familiar with in nature, such as the sound of ocean waves. This can be extremely useful as any issues, artifacts, and discrepancies in the frequency spectrum are easily perceived, not to mention the overall timbral balance.

Another great example of a ‘type’ of sound that can reveal a lot is a transient sound. By this, I mean any sound that is very sudden and loud, quickly rising in amplitude, and then rapidly decaying to silence. What comes to mind immediately are rhythmic sounds as opposed to tonal sounds, such as drum hits, claps, snaps etc. These types of sounds are extremely useful in discerning the sound of the “room”, or “space” of a given room (or virtual room, in this case). This is something that we as humans are quite attuned to in nature. Imagine standing and clapping in an open room, or a long hall, or a bathroom, or a closet, or a large cathedral. I would hazard a guess that you can imagine that clap sounding very different in those various rooms. This is due to the natural reverberation (reverb for short) in these various rooms, something affected by their size and dimensions, as well as the reflectivity of the surfaces in these rooms.

In contrast, with a sustained sound like a constantly strumming guitar, the sustained persistence of the sound makes it difficult to identify how the sound decays with time, which is the parameter that usually informs our subconscious understanding of what kind of room the sound is taking place in.

So, audio such as pink noise can reveal a lot about the frequency spectrum, and transient sounds such as drum hits or claps can reveal a lot about dynamics, and how the sound decays over time. Realistically however, there is a limit to how much one would want to listen to that kind of audio on repeat. So, to round off our selection of content, I would recommend just picking content that one is intimately familiar with.

Let’s conclude this section by talking about file formats. We recommend using lossless, high-quality audio, of atleast 48 Khz Sample Rate, and 24 Bit Depth.

It is also important to target a variety of channel formats – Mono (one channel), Stereo (two channels), 5.1, 7.1, and 7.1.4.

One trick that we found extremely useful is to take a few second long mono clip of say pink noise, or a Kick Drum or Snare Drum/Clap Sample and use an Audio Editor or Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) to create multichannel versions of that clip, with the audio isolated in a single channel, with the others populated with silence.

For example, we took a mono Kick Drum sample and created eight 7.1 variations of it. In each variant, the kick drum audio would be isolated to one channel, and the other seven would be populated with silence. We then repeated this process for stereo, 5.1, 7.1.4, and for other sounds such as pink noise, or other useful transient samples.

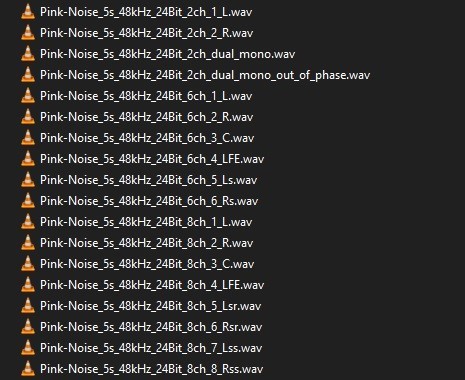

Pink Noise sample files for testing

For any transient samples, we would also recommend leaving 1-2 seconds of silence at the end of the clip, after the sound dies away. This leaves some room for you to actually hear the decay and reverb of the room.

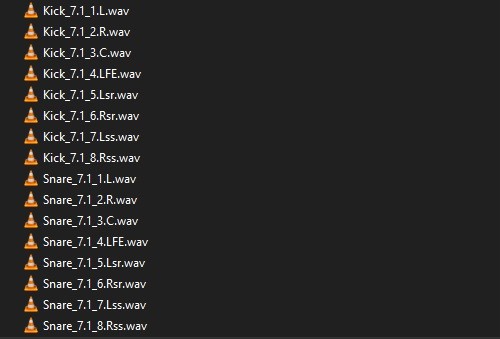

Transient Sound sample files for testing

We have uploaded some of these test files, including both 5.1 and 7.1 configurations of pink noise, and 7.1 samples including kick drum, snare, clap, and a hi-hat loop, for you to download, check out, and hopefully test with! You can find them here

Conclusion

Audio engineers have a variety of tools at their disposal, and a slate of curated content for a variety of purposes and use cases is essential. In this short piece we covered some of the key types of content that were necessary for this kind of evaluation and competitive analysis, specifically where spatial audio is concerned.

In the next part we will dive into the specifics of this evaluation framework and competitive analysis we have mentioned a few times already. This should give a clearer understanding of the different parameters we tested and listened for, as well as help to establish a guideline for WHAT to listen for.